The rising belief in Buddhism That spread greatly through India during the first and second centuries had spurred a renewed artistic fervor to illustrate the enlightened one and relay his message. During this prolific time emerged three main “schools” in India that had developed their own particular styles and distinctions. These were the Gandhara, Mathura, and Amaravati schools. Each region had fashioned their own technique in how they would portray the Buddha in their craft. Although, even with these differences there remained a set of distinctive parameters or lakshana that could easily define the piece as a Buddha notwitstanding what country you were in. In all there were thirty-two distinguishing features that needed to be expressed to give the piece validity. These ranged from specifying the color of the individual, to arm length, hand gestures and even identifying marks on the body such as wheels or chakras which are depicted on the palms of the hands.

Since those early explorations into Buddhist artwork the religion had gained much attention in neighboring countries and lands far away from its original inception. These places; such as Sri Lanka, China and Korea all needed to adopt their own “iteration” of their god as did the early Buddhists of India so long ago. In response to these countries need for icons, there is an amazingly similar approach to the tenets that the original schools practiced that has seemed to transcend time and culture while preserving much of the sentiment that was ingrained by the founding artisans from India’s past.

Sri Lanka

In the “Parinirvana of the Buddha” (9-35) a giant rock-cut statue of the Buddha is hewn from the side of a rock face. The Buddha is lying on his side and displays many Indian “markers” or traditional motives. The Piece has a soft and dreamy appearance that has no real hard or sharp lines of definition in the body or clothing lending a hallmark of the Mathura school of technique. The Buddha’s body is soft and gentle in appearance and only offers basic defining characteristics of the Buddha identity set. These features are consistent with an earlier piece done by Mathura trained artisans (9-14). This piece is further characterized by the light and almost non- existent presence of the clothing worn on the statue. It is only gently displayed through subtle lines that give a sense of the body shape beneath the robe itself. Also important to note is the facial features which take on an almost abstract appearance and delve away from perceptual realism. The hair’s abstract circle pattern and angled large oval eyes are less based in realism but more seated in conveying the intention of the piece to the viewer, again another indicator of the Mathura style. The overall intent and meaning to this piece is to impart the intensity and centrality of the theme in Buddhism while using the scale and abstract elements to convey the artist sentiment.

China

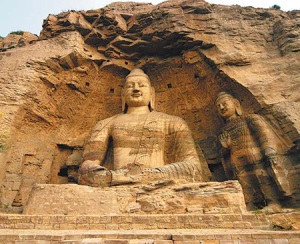

In “Seated Buddha, cave 20” (10-13) which is situated along a portion of the old “Silk Road” trade route in China. There is a large rock cut relief statue of the Buddha that initially resided inside a natural cave, but weathering has eroded the exterior fully exposing the work inside. This location along an inter-cultural “highway” most likely birthed this interpretation of Buddha by way of a subtle mixing of styles; Primarily the Gandhara and Mathura approaches. The clothing is a hybrid of either style because it does not have a harsh, set patterning like some Hellenistic pieces but it does still retain some rich, repetitive detail in the folding and mannerisms of worn clothing with an added amount of abstract embellishment. The facial structure more closely resembles the Gandhara style (9-13) in its sharper definition and more “Greek” move toward facial features. The nose and eye treatment closely resembles early Mediterranean art in its execution of more sharply defining facial contours in a conceptual manner. This is further compounded by the archaic smile of the Buddha that has been seen on many Greek artworks in the past. The overall softer body tones and shaping can obviously be attributed to the Mathura style as well as the overall presentation is not as precise or discerning in proportion as some other Gandhara works.

Korea

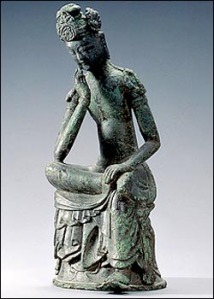

In the “Bodhisattva Seated in Meditation” (10-27) we have a good example of a Korean art work patterning itself in the style of the Amaravati School. Here a slight and slender portrayal of a Bodhisattva is seated in deep (as well as joyful?) meditation. This is very similar to the third school of Buddhist Indian artwork in the depiction of these more thinly bodied and delicately appointed figures. The treatment of the garments associated settings has a conceptual feel while simultaneously exuding a light and vibrant energy through the forms. This art feels free and expressive but not bound to scrutinous detail which it does not need to relay its concept. Overall, the piece’s lacking of “trained detail” as in past examples finds itself as a fresh approach which has an uplifting and gentle feel.